Silk: Caroline's Story;Tapestry: A Lowcountry Rapunzel; and Homespun.

My Blog:

Saturday, September 3, 2022

'Tapestry' Named a Southern Fiction Finalist

Wednesday, August 17, 2022

Deb Stratas Interviews Sophia Alexander

Monday, August 1, 2022

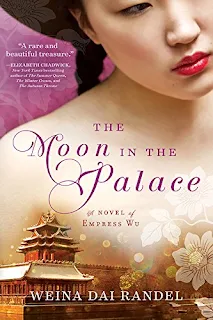

'The Moon in the Palace' by Weina Dai Randel: the Story of a Far-from-Clever Concubine

The Moon in the Palace by Weina Dai Randel is beautifully written, even poetic at times, but while seventh-century China and the first few pages of the novel intrigued me, they perhaps set my expectations too high: I ended up quite disappointed with the story and with Mei.

Our protagonist is meant to rule China, we’re told by a wise astrologer. She conscientiously studies a revered text, The Art of War. She even writes a riddle that catches the attention of the emperor (never mind that the answer is a bit clichéd in literature at this point). Mei is not as obsessed with feminine trappings as the other beautiful, noble girls called to the palace. Of course not—she’s got more important things on her mind. The other girls are mean to her, though, and there Randel depicts the cattiness of the court, the competition there—but we soothe ourselves that she has at least made one friend.

Up until this point, Randel still has me. I found it unwise, I suppose, that Mei didn’t try to learn from the other young women, that she didn’t try harder to fit in and ‘get picked’ by the emperor, since that was her objective. Randel seemed to want to show that Mei wasn’t as vain as the other girls. Since being beautiful was essentially her job, however, she shows a dereliction of duty—or at least an obtuseness I didn’t think the author meant to portray. Mei crosses the line, in my opinion, when the emperor sends her scents and such before she is supposed to come to meet with him, and she simply gives them away to her friends. The reader is perhaps supposed to think that Mei is being clever in trying to secure their favor, but it seemed an insult to the emperor, given the scenario.

Her relative friendlessness could endear her to us, but Mei doesn’t seem to feel it much—and doesn’t seem to try very hard to befriend the others. The most beautiful woman there, Jewel, is at least Mei’s friend, and we attach ourselves to that friendship, as nothing else is going very well for Mei. So when Jewel betrays Mei shockingly, the reader resents that the author didn’t lay out more obvious hints. Not only that, but Mei then has no friends at all in a court full of girls, which makes Mei seem frankly unlikable—especially as Mei doesn’t seem to care for them, either. When Mei later makes friends with two young women at the inner court, they seem more ‘useful’ than friends of the heart.

So… if Mei were brilliant and honed in on her objective with a laser focus, we could still read with awe, admiring her. But no, we’re disappointed again and again. She doesn’t repeat the hackneyed riddle scene ever, except for instantaneously coming up with a lovely poem once—but it was on the heels of another woman expressing her anguish, which didn’t sit so well. She steals a fellow she barely knows from yet another woman—though granted, the ratio of women to men is highy skewed, so the reader can shrug it off as perhaps inevitable. Then, however, the worst scene of the book unfolds: the late empress’s crowns and jewels are stolen from under Mei’s watch and she profoundly disappoints, seeming incredibly dim-witted compared with what we’d been built up to expect.

I cannot fathom what Randel was thinking. First she sends Mei alone to confront Jewel, who has tricked Mei before, but Mei doesn’t let anyone else know what’s happened. She doesn’t call for guards to search Jewel’s quarters. Instead, she essentially lets Jewel know she’s on to her so that Jewel has ample time to securely stow the jewels away from her own quarters. While Mei is there, Jewel demands that Mei kill all the precious silkworms before she’ll give the jewels back. Stupidly, Mei goes to commit that treasonable offense. She’s seen by guards and the Noble Lady, barely convincing them to allow her into the highly protected space, so there could be no question who had committed this treason. Thus not only does Mei attempt to betray the Noble Lady AND the emperor (not to mention murdering countless silkworms), she never once even seems to consider that Jewel is simply setting her up for a downfall even worse than the one Mei worries will come to the Noble Lady. So here we realize—if the author does not—that Mei is not only a ready traitor but is far from clever. Would she have even realized Jewel was setting up the Noble Lady if Jewel hadn’t told her?

Why keep reading? Well, the action does keep flowing along, and Randel does have lovely descriptions. We want to see what happens.

Another point of frustration for the reader is that Mei continues to witness cruel acts and countless murders of innocents by the emperor’s direct orders, but she never once tries to help stop them or prevent future barbarisms. Perhaps Randel simply meant to depict how perilous court life was, that Mei shouldn’t dare step out of line. I’m not sure what Mei could have actually done for those victims, but I hoped that such a supposedly clever girl would figure out how to use her position to exert some positive influence—but she doesn’t, not through being an inspiring paragon of virtue nor through some brilliant trickery. Nothing. Compounding this is the fact that Mei actually does step out of line—continually—but for no sensible reason. It’s never to help anyone, at least not from a sensible person’s perspective. When the palace is attacked and her besotted fellow risks himself and his mission to take the time to inform her, to insist that she go hide at once, she puts herself in the midst of danger for no good reason, repeatedly. She eventually warns the emperor—only because she’s worried about her fellow—but the reader wonders why bother. The emperor is a ruthless, deranged man who came to power by murdering his own family, and perhaps she should support the overthrow instead.

I haven’t even much mentioned the pivotal relationship between Mei and the old emperor. Randel sets us up fairly early in the novel to brace for a sex scene between them. The setups were surprising and recurred often, never the same. The writing was good, but I take issue with the fact that I was never clear whether they ever successfully had sex at all. When Mei does have sex with her fellow, I don’t even know if she’s a virgin or not. Since sexual relations with the emperor were key to Mei’s objective, it was remiss to leave out that information.

Overall, I don’t recommend this novel. Mei is not kind nor really clever—she’s not inspirational in any way, nor particularly likable. She’s inconsistent, too: for instance, she’s bothered by cruelty to animals (doing nothing to stop it, of course) but has utter disdain for when she is served tofu instead of meat on her plate. Her goals end up seeming pointless. However, Randel’s writing itself is of fairly good quality, and the story and setting are interesting, action-packed. If I find myself without anything else to listen to, I may pass the time with the sequel just to see what happens next for Mei… but I doubt it.

Friday, July 29, 2022

'Wuthering Heights' by Emily Brontë is a Mad and Passionate Masterpiece

|

| Sophia Alexander (me!) with my old copy of Wuthering Heights |

Wuthering Heights was Emily Brontë’s only published novel, crammed with all of her intensity, passion, and verve, seemingly! I’ve read it for my first time as a grownup, just before her 204th birthday on July 30th (she was born in 1818 in Yorkshire, England, almost exactly a year after Jane Austen's death. Hmm...). What a voice. I’m going to critique her, however, just as I critiqued Jane Austen (heresy!), but first let me say that this book is a masterpiece.

I can honestly claim that I’ve never read a

book with more caustic characters, as a whole. Fascinating, sometimes even with a biting sense of humor.

“Look here Joseph,” [Cathy] continued, taking a long, dark book from a shelf. “I’ll show you how far I’ve progressed in the Black Art: I shall soon be competent to make a clear house of it. The red cow didn’t die by chance; and your rheumatism can hardly be reckoned among providential visitations!”

“Oh, wicked, wicked!” gasped the elder….

I thought her conduct must be prompted by a species of dreary fun.

And so must Emily’s readers think! At least at times. Other times, it's a bit more brutal and heartrending.

Perhaps my biggest critique of Emily’s actual writing is that her

female characters keep developing nearly the same character eventually (excluding

Nelly). For example, Isabella Linton is supposed to be far milder than

Catherine, but she becomes just as impudent as Catherine after Catherine’s

death. Young Cathy (Catherine’s

daughter) follows the same pattern. Mind that I find their saucy tongues quite entertaining, and perhaps I

should give Emily the benefit of the doubt: she may have meant to represent

that under trying, abusive circumstances, sweet, cultivated women will all

become a bit mad!

I’m blown away far more this time than when I read it as a girl—both times the same copy, a now falling-apart Watermill Classic paperback edition, put out in 1983, that I received with my Troll book order at school. I still find it odd that books can be reprinted with no notation on the copyright page of the original publication date. At least this edition does mention in the About the Author section that Wuthering Heights was actually first published in 1847. Emily would likely have produced many other great works if she hadn’t died the next year in 1848, age 30—her life snuffed out all too early, like so many of the novel’s characters. In fact, it almost seems that someone was truly making a ‘clear house of it’ for all the Brontë’s around this time.

Even though I think it a monumental work of art now, what I recall most about it from my girlhood is arguing that Jane Eyre, by Emily’s older sister, was a far better story (my own younger sister disagreed). I suppose I should probably reread Jane Eyre now, too, to see if I still feel the same way! At the time, I found it difficult to connect with the characters in Emily’s novel of eccentrics, whereas I completely identified with poor, relatable Jane Eyre. The only truly reasonable person in Wuthering Heights seems to be the motherly housekeeper Nelly Dean, who serves as the narrator of much of the story, and I certainly didn’t identify with her as a preteen. Perhaps not so much now, either, but more than before. I can also relate to the passions of the characters better, too, of course. Overall, though, I regard Wuthering Heights as gripping, highly dramatized entertainment in comparison with, say, the social realism of Jane Austen.

|

| Emily Brontë |

Now, as I so like to do, let's shift gears a bit to chat about possible

inspirations:

First, there is the fairly shocking incident of Catherine’s coffin

side being removed so that their bodies could lie together in the grave. This is perhaps inspired by a true story: King George II commanded similarly for his wife Caroline’s coffin--for the side

of it to be removable so that his coffin to adjoin hers. She predeceased him, and

he wanted to eventually lie with her in their resting place, undivided for the

rest of eternity (he died in 1760). So perhaps that true story inspired

Emily!

I mentioned before in my blog about Northanger Abbey

how Wuthering Heights seemed to have been inspired at least in part by the protagonist Catherine’s

character, especially, even having the same name—only, ironically, it’s set a

little before Northanger Abbey, as if it could be Northanger Abbey’s

inspiration!

The relatively happy situation at the end of Wuthering

Heights for Cathy reminded me of a similar romantic scenario in one of my

favorite novels (at least it’s a favorite book beginning), I Capture the Castle

by Dodie Smith, in which a young, scorned farmhand turns out to be far more

intelligent than he seems at first. Hmm,

that also makes one think of the film The Princess Bride, which takes it

to an entirely different level!

Finally, consider Linton Heathcliff, Cathy’s whiny, spindly

cousin, as the inspiration for the young, crippled master of the manor, Colin Craven (Mary’s

cousin), in The Secret Garden (1911) by Frances Hodgson Burnett.

I truly enjoyed Wuthering Heights—Emily Brontë’s

singular lifetime achievement. She accomplished in her twenties what most

writers can never achieve. What a stunning cast of characters. What an

impossibly passionate tale.

Tuesday, July 26, 2022

Don't Be a Sheep When You Read 'Excellent Sheep', Though William Deresiewicz Eventually Has One or Two Good Points

I recommend that you skip Excellent Sheep by William Deresiewicz altogether, even though there's a decent section in the middle (but I'll give you the scoop on that). Here's the rundown:

First, this retired Yale professor blames the general worsening of mental health in this country on the curricula of the Ivy League schools! I suppose he really is focusing on Ivy League students, but he seems unaware that mental health is worsening across the board for young people, especially--and of course those under high pressure are going to experience some of the brunt of it. He doesn't acknowledge causes like the rampant use of technology, especially screen time, endocrine disruptors in our environment, or a myriad of other potential causes. Instead, Dr. Deresiewicz is ready to dismantle the rigorous curricula that some of the most brilliant minds in our country have developed over centuries, when that's precisely what these students are there for! They've worked so hard to get there, to receive that education, yet he seems to advocate undoing that Ivy League rigor when instead they could just ease the grading system (see below, 4th paragraph from the end for more on that). Sure, the curricula are not static; they've changed over time and must continue adapting as necessary, but I repeat: a rigorous education is what students are there for in the first place. Perhaps it's simply not for everyone--and certainly there will be individual courses that are completely unreasonable in their demands and far too stressful, but these should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. And of course the schools should do their best to provide adequate mental health services for their students, especially given the pressures they are under.

The tirade that Dr. Deresiewicz let out against parents of Ivy Leaguers was frankly offensive, and I'm not even one of them! He speaks as if they are all atrocious parents and in the wrong. Hmm. Apparently he spent too many years listening to his students' frustrations with their parents and being annoyed by their intrusions upon himself--and he lets it out here in a way that I suspect is fed by his own ingratitude towards and resentment towards his own excellent parents. I found it rather intolerable to listen to. Talk about 'privileged'! He's rarely been around students, I suspect, whose parents were neglectful or uninvolved. Not to say that he doesn't have a point that the kids' feelings of worth are perhaps too wrapped up in their success and GPA and such, but he is coming from such a place of bias that it's difficult to swallow his contempt for these remarkable parents. (I say they're remarkable because of how spectacular their kids have turned out--despite the students' sometimes endless complaints about mom and dad, no doubt--and not remotely because of anything this professor said.)

The book does get better, briefly:

Around the middle of the book, he begins to discuss the value of reading, and so of course I'm jolted on board, at least for a bit! He refers to a quote that majoring in English is like majoring in finding yourself, or something lovely like that. To be honest, however, as much as I adore novels, I never took the first English class in college, as I'd placed out with AP credits. My daughter has a strange aversion to taking English courses herself, saying that she doesn't want anyone else selecting what novels she reads. Hah, so while I meant to praise what he had to say there, I'm not sure my experience reflects how it relates to college life and curricula, exactly. Even he says that we should curate our own reading lists, as only we know what we are drawn to, what will connect for us. I'm paraphrasing broadly. [Note that he actually does have another book out about getting A Jane Austen Education, and I actually did read all her books one summer while in college, so perhaps he wouldn't have curated my reading list too far off!]

He also talks about the value of the liberal arts in creating well-rounded thinkers. I've heard this before, but suddenly it hit home. Perhaps it was how well he expressed and supported it. Perhaps it was because he cited figures that suggest that businesses are looking for those thinkers, actually preferring them oftentimes. He discusses how it takes years and years to obtain that broad background, to learn to think constructively, whereas hard skills can be taught pretty quickly. If his statistics hold up, then they should allay some of our worries about the liberal arts degrees not being so 'practical'--though I'd still want to do some of my own research on that, if practicality and a high income are truly the priority. [On this note, I'd like to interject that he also has a book out called, The Death of the Artist: How Creators Are Struggling to Survive in the Age of Billionaires and Big Tech. Just sayin'.] [Also, knowing how complex entire fields of science are, with so much depth and breadth, it's hard for me to understand how liberal arts majors could possibly just 'step into it'. I'm aware that some do, going straight to medical school with their English degrees, but I'm convinced they must be geniuses!]

Personally, I was both a science major AND advocate a liberal arts education. I'm particularly keen on the social sciences, in retrospect. I was so zoned in on my biochemistry major that I only took social science classes to meet the core liberal arts requirements, yet it turns out they were some of the most world-view-changing courses in my undergraduate career--especially World Religions and Anthropology (I didn't even know what a hunter-gatherer was before that course!). While we'd like to think we did most of our educational rounding-out in childhood, I, for one, very much needed that liberal arts college curriculum.

Towards the end of the book, Dr. Deresiewicz actually does start to convince me that the Ivy Leagues may not provide the best education for our brightest students, and it's specifically when he talks about the pressure on professors to do research and publish. I have seen that for myself, that professors' priorities are often not the students, and they increasingly use professional jargon in their teaching, rather than plain speak. It's a bit akin to doctors working for the insurance companies, not the patients.

However, these bright points in the very middle of the book almost belie the rest of the manuscript. Though he talks about the benefits of a liberal arts education here, he later insists that these hard-working students are in no way truly brighter, superior, more deserving, any of it... and while, of course, every person has inherent worth, and grades are not everything, he seems to be maligning their accomplishments out of resentment of their self-conceived 'superiority'. In fact, he relates how he would tear them down if he were their commencement speaker (he doesn't call it that, but if you listen to what he says, that's what it is). Not that it's not good to be mindful of all the ways we are lucky and blessed, and that could be a component of it, but I do hope he is never invited to deliver a commencement speech, as those hard-working students do not deserve his contempt, especially at their very graduation ceremony.

I don't agree with Dr. Deresiewicz about the quality of the students not being a draw at the Ivy Leagues [for goodness sakes, he was even pointing out how Harvard dropouts Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerburg made important connections that helped them professionally while there--and I wouldn't cry if they'd been my son's roommates at college, either!], but I certainly feel that he has a point about some of our smaller universities having wonderful instructors more focused on the students. His recommendation to look at some of the better liberal arts colleges struck me as excellent advice for equipping our college students to face life with a broad knowledge base and the ability to think and interact intellectually--and without such pressure. This was not actually a motivating force in considering colleges for my own children, and I may have viewed the college choices a bit differently if I'd heard this audiobook when we were considering colleges for them. That said, once that nice liberal arts foundation has been assured at a good school, I still think rankings do matter--mostly in view of the other students our own children will be around, their influences.

I am frankly alarmed by his insistence that we 'even the playing field' by not crediting students with any achievements that their parents' money helped to acquire. He talks about handicapping their applications while giving extra points to needier students, willy-nilly. For all his insistence on not feeling superior, on not demeaning the 'other', he sure isn't very sympathetic to the hard-working Ivy League candidates that come from families that were able and devoted to supporting them.

In fact, I find it telling that he bemoans these 4.0+ GPA high school students averaging 3.3 GPAs at their Ivy League Schools, as if they don't deserve it. First he's so alarmed about them being pushed too hard, wailing about their mental health, but then he wants to push them even harder, undeservedly? No, I really don't think he is an advocate for his former students much at all, aside from those who serve his purpose by resenting real and perceived deficits of their Ivy League educations and experiences. I'd personally suggest that the Ivy Leagues actually shift to a Pass/Fail system, since they have already ensured that their students are top-notch. My graduate school did this, and it certainly took a tremendous pressure off both me and my instructors: I stopped worrying about arguing if I thought I should get credit for a question or two, so concerned about that 'A'. Instead, I glanced at my test, saw that I did fine, and moved on with my life (and the teacher could, too!). It helps reduce stress immensely. I was also more free to focus on my areas of interest.

He disparages the idea of charity 'service' as a superiority mindset--an argument that may have some merit, though hopefully students and listeners are not dissuaded from still trying to do good, from participating in important charity work. Instead, he suggests students transfer from the Ivy League schools to state universities and take service jobs, like working in restaurants. What terrible advice, at least the first part. However, he does have a point that perhaps one of the best ways for privileged young people to develop true empathy and a better sense of equality with those who do manual labor and service work is to do at least a stint of it for themselves. I have seen this be eye-opening more than once. So... it might not be the worst idea to require such service-industry work from nearly every Ivy League student, probably no more than part-time for a semester, but I think it would improve their consideration for service-industry workers in general, at least. So, it seems there is a seed or two of wisdom amidst Dr. Deresiewicz's overall bad advice.

One last bit of truth to Dr. Deresiewicz's book is this: that the Ivy Leagues like to tout their selective acceptance rates, so they market to loads of young people that they know don't stand a chance, just to achieve those numbers. Frankly, though Dr. Deresiewicz doesn't himself go over it, I learned from an admission officer's book that you can't just be a perfect student with perfect scores--you either must be obviously disadvantaged or have achieved something truly remarkable [or simply 'remarkable' if it fits a specific niche that they're having difficulty filling] or be from a legacy family; yet even she didn't acknowledge the cruelty of marketing to and wasting the time and resources of the very best and brightest across the country--and of disappointing them. If they believe they actually stand a chance of getting in, if they've been actively recruited to apply, then they are going to feel acute rejection when they are rejected by this dream school, when there actually was no true rejection, as they never stood a chance in the first place. It's a cruel trick and one to be mindful of if we're truly concerned about their mental health.

So, my advice is to skip this book and probably to skip the Ivy League application as well, unless you are a celebrity or a minority (with a perfect academic record) or a potential legacy student, something of that nature, anyhow. My best takeaway from this book is to seriously consider a liberal arts college no matter the major, 'practical' choice or not.

Tuesday, July 12, 2022

Literary Titan Thrice Honors 'Silk', Too!

"[I]t’s important to try to understand where others are coming from, to develop empathy—even for those with bats in their belfry, as Anne would say." -from my interview for 'Silk' with Literary Titan.

Check it out https://literarytitan.com/2022/06/25/a-dramatic-re-interpretation/

“Dr. Conner and Clayton Bell are prime examples of the class differences in the Carolinas… readers will be torn between who is the favorite and who should end up with Caroline. It is a whirlwind following the three of them and watching Jessie maneuvering in the background… There is never a dull moment in the plot. The descriptions are vivid, and you feel like you are there in the old south, experiencing the changes in the society as they happen.” -Literary Titan, 5-star review.

Sunday, July 10, 2022

One Year In, So Much Love!

Here are some of my favorite professional review snippets and awards for Silk and Tapestry thus far...