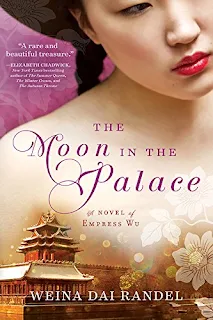

The Moon in the Palace by Weina Dai Randel is beautifully written, even poetic at times, but while seventh-century China and the first few pages of the novel intrigued me, they perhaps set my expectations too high: I ended up quite disappointed with the story and with Mei.

Our protagonist is meant to rule China, we’re told by a wise astrologer. She conscientiously studies a revered text, The Art of War. She even writes a riddle that catches the attention of the emperor (never mind that the answer is a bit clichéd in literature at this point). Mei is not as obsessed with feminine trappings as the other beautiful, noble girls called to the palace. Of course not—she’s got more important things on her mind. The other girls are mean to her, though, and there Randel depicts the cattiness of the court, the competition there—but we soothe ourselves that she has at least made one friend.

Up until this point, Randel still has me. I found it unwise, I suppose, that Mei didn’t try to learn from the other young women, that she didn’t try harder to fit in and ‘get picked’ by the emperor, since that was her objective. Randel seemed to want to show that Mei wasn’t as vain as the other girls. Since being beautiful was essentially her job, however, she shows a dereliction of duty—or at least an obtuseness I didn’t think the author meant to portray. Mei crosses the line, in my opinion, when the emperor sends her scents and such before she is supposed to come to meet with him, and she simply gives them away to her friends. The reader is perhaps supposed to think that Mei is being clever in trying to secure their favor, but it seemed an insult to the emperor, given the scenario.

Her relative friendlessness could endear her to us, but Mei doesn’t seem to feel it much—and doesn’t seem to try very hard to befriend the others. The most beautiful woman there, Jewel, is at least Mei’s friend, and we attach ourselves to that friendship, as nothing else is going very well for Mei. So when Jewel betrays Mei shockingly, the reader resents that the author didn’t lay out more obvious hints. Not only that, but Mei then has no friends at all in a court full of girls, which makes Mei seem frankly unlikable—especially as Mei doesn’t seem to care for them, either. When Mei later makes friends with two young women at the inner court, they seem more ‘useful’ than friends of the heart.

So… if Mei were brilliant and honed in on her objective with a laser focus, we could still read with awe, admiring her. But no, we’re disappointed again and again. She doesn’t repeat the hackneyed riddle scene ever, except for instantaneously coming up with a lovely poem once—but it was on the heels of another woman expressing her anguish, which didn’t sit so well. She steals a fellow she barely knows from yet another woman—though granted, the ratio of women to men is highy skewed, so the reader can shrug it off as perhaps inevitable. Then, however, the worst scene of the book unfolds: the late empress’s crowns and jewels are stolen from under Mei’s watch and she profoundly disappoints, seeming incredibly dim-witted compared with what we’d been built up to expect.

I cannot fathom what Randel was thinking. First she sends Mei alone to confront Jewel, who has tricked Mei before, but Mei doesn’t let anyone else know what’s happened. She doesn’t call for guards to search Jewel’s quarters. Instead, she essentially lets Jewel know she’s on to her so that Jewel has ample time to securely stow the jewels away from her own quarters. While Mei is there, Jewel demands that Mei kill all the precious silkworms before she’ll give the jewels back. Stupidly, Mei goes to commit that treasonable offense. She’s seen by guards and the Noble Lady, barely convincing them to allow her into the highly protected space, so there could be no question who had committed this treason. Thus not only does Mei attempt to betray the Noble Lady AND the emperor (not to mention murdering countless silkworms), she never once even seems to consider that Jewel is simply setting her up for a downfall even worse than the one Mei worries will come to the Noble Lady. So here we realize—if the author does not—that Mei is not only a ready traitor but is far from clever. Would she have even realized Jewel was setting up the Noble Lady if Jewel hadn’t told her?

Why keep reading? Well, the action does keep flowing along, and Randel does have lovely descriptions. We want to see what happens.

Another point of frustration for the reader is that Mei continues to witness cruel acts and countless murders of innocents by the emperor’s direct orders, but she never once tries to help stop them or prevent future barbarisms. Perhaps Randel simply meant to depict how perilous court life was, that Mei shouldn’t dare step out of line. I’m not sure what Mei could have actually done for those victims, but I hoped that such a supposedly clever girl would figure out how to use her position to exert some positive influence—but she doesn’t, not through being an inspiring paragon of virtue nor through some brilliant trickery. Nothing. Compounding this is the fact that Mei actually does step out of line—continually—but for no sensible reason. It’s never to help anyone, at least not from a sensible person’s perspective. When the palace is attacked and her besotted fellow risks himself and his mission to take the time to inform her, to insist that she go hide at once, she puts herself in the midst of danger for no good reason, repeatedly. She eventually warns the emperor—only because she’s worried about her fellow—but the reader wonders why bother. The emperor is a ruthless, deranged man who came to power by murdering his own family, and perhaps she should support the overthrow instead.

I haven’t even much mentioned the pivotal relationship between Mei and the old emperor. Randel sets us up fairly early in the novel to brace for a sex scene between them. The setups were surprising and recurred often, never the same. The writing was good, but I take issue with the fact that I was never clear whether they ever successfully had sex at all. When Mei does have sex with her fellow, I don’t even know if she’s a virgin or not. Since sexual relations with the emperor were key to Mei’s objective, it was remiss to leave out that information.

Overall, I don’t recommend this novel. Mei is not kind nor really clever—she’s not inspirational in any way, nor particularly likable. She’s inconsistent, too: for instance, she’s bothered by cruelty to animals (doing nothing to stop it, of course) but has utter disdain for when she is served tofu instead of meat on her plate. Her goals end up seeming pointless. However, Randel’s writing itself is of fairly good quality, and the story and setting are interesting, action-packed. If I find myself without anything else to listen to, I may pass the time with the sequel just to see what happens next for Mei… but I doubt it.

No comments:

Post a Comment