Tapestry: A Lowcountry Rapunzel, the second book of The Silk Trilogy, is a recipient of the IndieBRAG medallion. Yay! For those of you who aren't yet familiar with my books, it's the sequel to Silk: Caroline's Story (also an IndieBRAG medallion honoree). In Tapestry, a pair of resilient Southern sisters face separation and trauma at the hands of their sociopathic stepmother, yet find their way, despite everything.

Tapestry: A Lowcountry Rapunzel, the second book of The Silk Trilogy, is a recipient of the IndieBRAG medallion. Yay! For those of you who aren't yet familiar with my books, it's the sequel to Silk: Caroline's Story (also an IndieBRAG medallion honoree). In Tapestry, a pair of resilient Southern sisters face separation and trauma at the hands of their sociopathic stepmother, yet find their way, despite everything.

Silk: Caroline's Story;Tapestry: A Lowcountry Rapunzel; and Homespun.

My Blog:

Tuesday, September 13, 2022

'Tapestry' Honored with the IndieBRAG Medallion

Friday, September 9, 2022

Farewell to a Classy Queen

A few years ago I found this plate commemorating the belated

queen’s 1953 coronation in a pawn shop somewhere. Around her portrait are Latin

words meaning ‘Queen Elizabeth II by the grace of God’. Though it was produced

at Royal Staffordshire Ceramics in Berslum, England, shields with the flags of

the provinces of Canada are depicted around it.

Canada is just one of 54 countries within the British Commonwealth, which

enfolds over a quarter of the nations around the world and almost one-third of

the world population. Elizabeth will be mourned the world over, if not by

everyone. I personally found it a

comfort to listen to her Christmas addresses, as she seemed one of the few

leaders to exhibit thoughtfulness, respectfulness, and diplomacy in an age

predominated by brash, narcissistic politicians. We lost a dedicated, classy

world leader yesterday. So grateful that she lived to the age of ninety-six,

swearing in the UK’s new prime minister only days ago. May we all function so

vitally until the ends of our lives.

Thursday, September 8, 2022

'Welcome to the Hamilton' by Tanya E. Williams

"Whatever the situation, the place where you find yourself is simply a new location from which to begin again."

-advice from Tanya E. Williams' character Ruby/'Cookie', assistant to the pastry chef.Welcome to the Hamilton is the most heartwarming novel by Tanya E. Williams to date. I especially appreciated the unusual perspective of a young woman aspiring to be a maid in a fine establishment. It’s an idea I can hardly fathom, even still, but the endeavor was quite the calisthenic for my mind! Certainly a fresh outlook. Yes, Clara was trying to get the job out of desperation, but Williams embraced the spirit of the 1920s era, the charm of ‘independence’ in earning her own money, of being part of the grandeur of such a magnificent establishment. Hardworking Clara was quite flawed in how she condemned many of those around her (both judgmental and jealous), but she continually caught herself at it. By the end of the novel she was vastly improved—and even more tolerant than I would be (once some of her initial uncharitable assumptions had indeed proven to be true). Williams’ intrinsically kind nature shines through in this novel, an unexpected treasure.

Saturday, September 3, 2022

'Tapestry' Named a Southern Fiction Finalist

Wednesday, August 17, 2022

Deb Stratas Interviews Sophia Alexander

Monday, August 1, 2022

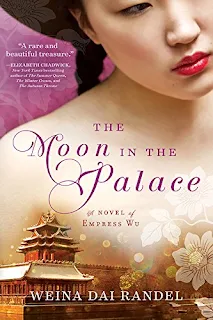

'The Moon in the Palace' by Weina Dai Randel: the Story of a Far-from-Clever Concubine

The Moon in the Palace by Weina Dai Randel is beautifully written, even poetic at times, but while seventh-century China and the first few pages of the novel intrigued me, they perhaps set my expectations too high: I ended up quite disappointed with the story and with Mei.

Our protagonist is meant to rule China, we’re told by a wise astrologer. She conscientiously studies a revered text, The Art of War. She even writes a riddle that catches the attention of the emperor (never mind that the answer is a bit clichéd in literature at this point). Mei is not as obsessed with feminine trappings as the other beautiful, noble girls called to the palace. Of course not—she’s got more important things on her mind. The other girls are mean to her, though, and there Randel depicts the cattiness of the court, the competition there—but we soothe ourselves that she has at least made one friend.

Up until this point, Randel still has me. I found it unwise, I suppose, that Mei didn’t try to learn from the other young women, that she didn’t try harder to fit in and ‘get picked’ by the emperor, since that was her objective. Randel seemed to want to show that Mei wasn’t as vain as the other girls. Since being beautiful was essentially her job, however, she shows a dereliction of duty—or at least an obtuseness I didn’t think the author meant to portray. Mei crosses the line, in my opinion, when the emperor sends her scents and such before she is supposed to come to meet with him, and she simply gives them away to her friends. The reader is perhaps supposed to think that Mei is being clever in trying to secure their favor, but it seemed an insult to the emperor, given the scenario.

Her relative friendlessness could endear her to us, but Mei doesn’t seem to feel it much—and doesn’t seem to try very hard to befriend the others. The most beautiful woman there, Jewel, is at least Mei’s friend, and we attach ourselves to that friendship, as nothing else is going very well for Mei. So when Jewel betrays Mei shockingly, the reader resents that the author didn’t lay out more obvious hints. Not only that, but Mei then has no friends at all in a court full of girls, which makes Mei seem frankly unlikable—especially as Mei doesn’t seem to care for them, either. When Mei later makes friends with two young women at the inner court, they seem more ‘useful’ than friends of the heart.

So… if Mei were brilliant and honed in on her objective with a laser focus, we could still read with awe, admiring her. But no, we’re disappointed again and again. She doesn’t repeat the hackneyed riddle scene ever, except for instantaneously coming up with a lovely poem once—but it was on the heels of another woman expressing her anguish, which didn’t sit so well. She steals a fellow she barely knows from yet another woman—though granted, the ratio of women to men is highy skewed, so the reader can shrug it off as perhaps inevitable. Then, however, the worst scene of the book unfolds: the late empress’s crowns and jewels are stolen from under Mei’s watch and she profoundly disappoints, seeming incredibly dim-witted compared with what we’d been built up to expect.

I cannot fathom what Randel was thinking. First she sends Mei alone to confront Jewel, who has tricked Mei before, but Mei doesn’t let anyone else know what’s happened. She doesn’t call for guards to search Jewel’s quarters. Instead, she essentially lets Jewel know she’s on to her so that Jewel has ample time to securely stow the jewels away from her own quarters. While Mei is there, Jewel demands that Mei kill all the precious silkworms before she’ll give the jewels back. Stupidly, Mei goes to commit that treasonable offense. She’s seen by guards and the Noble Lady, barely convincing them to allow her into the highly protected space, so there could be no question who had committed this treason. Thus not only does Mei attempt to betray the Noble Lady AND the emperor (not to mention murdering countless silkworms), she never once even seems to consider that Jewel is simply setting her up for a downfall even worse than the one Mei worries will come to the Noble Lady. So here we realize—if the author does not—that Mei is not only a ready traitor but is far from clever. Would she have even realized Jewel was setting up the Noble Lady if Jewel hadn’t told her?

Why keep reading? Well, the action does keep flowing along, and Randel does have lovely descriptions. We want to see what happens.

Another point of frustration for the reader is that Mei continues to witness cruel acts and countless murders of innocents by the emperor’s direct orders, but she never once tries to help stop them or prevent future barbarisms. Perhaps Randel simply meant to depict how perilous court life was, that Mei shouldn’t dare step out of line. I’m not sure what Mei could have actually done for those victims, but I hoped that such a supposedly clever girl would figure out how to use her position to exert some positive influence—but she doesn’t, not through being an inspiring paragon of virtue nor through some brilliant trickery. Nothing. Compounding this is the fact that Mei actually does step out of line—continually—but for no sensible reason. It’s never to help anyone, at least not from a sensible person’s perspective. When the palace is attacked and her besotted fellow risks himself and his mission to take the time to inform her, to insist that she go hide at once, she puts herself in the midst of danger for no good reason, repeatedly. She eventually warns the emperor—only because she’s worried about her fellow—but the reader wonders why bother. The emperor is a ruthless, deranged man who came to power by murdering his own family, and perhaps she should support the overthrow instead.

I haven’t even much mentioned the pivotal relationship between Mei and the old emperor. Randel sets us up fairly early in the novel to brace for a sex scene between them. The setups were surprising and recurred often, never the same. The writing was good, but I take issue with the fact that I was never clear whether they ever successfully had sex at all. When Mei does have sex with her fellow, I don’t even know if she’s a virgin or not. Since sexual relations with the emperor were key to Mei’s objective, it was remiss to leave out that information.

Overall, I don’t recommend this novel. Mei is not kind nor really clever—she’s not inspirational in any way, nor particularly likable. She’s inconsistent, too: for instance, she’s bothered by cruelty to animals (doing nothing to stop it, of course) but has utter disdain for when she is served tofu instead of meat on her plate. Her goals end up seeming pointless. However, Randel’s writing itself is of fairly good quality, and the story and setting are interesting, action-packed. If I find myself without anything else to listen to, I may pass the time with the sequel just to see what happens next for Mei… but I doubt it.

Friday, July 29, 2022

'Wuthering Heights' by Emily Brontë is a Mad and Passionate Masterpiece

|

| Sophia Alexander (me!) with my old copy of Wuthering Heights |

Wuthering Heights was Emily Brontë’s only published novel, crammed with all of her intensity, passion, and verve, seemingly! I’ve read it for my first time as a grownup, just before her 204th birthday on July 30th (she was born in 1818 in Yorkshire, England, almost exactly a year after Jane Austen's death. Hmm...). What a voice. I’m going to critique her, however, just as I critiqued Jane Austen (heresy!), but first let me say that this book is a masterpiece.

I can honestly claim that I’ve never read a

book with more caustic characters, as a whole. Fascinating, sometimes even with a biting sense of humor.

“Look here Joseph,” [Cathy] continued, taking a long, dark book from a shelf. “I’ll show you how far I’ve progressed in the Black Art: I shall soon be competent to make a clear house of it. The red cow didn’t die by chance; and your rheumatism can hardly be reckoned among providential visitations!”

“Oh, wicked, wicked!” gasped the elder….

I thought her conduct must be prompted by a species of dreary fun.

And so must Emily’s readers think! At least at times. Other times, it's a bit more brutal and heartrending.

Perhaps my biggest critique of Emily’s actual writing is that her

female characters keep developing nearly the same character eventually (excluding

Nelly). For example, Isabella Linton is supposed to be far milder than

Catherine, but she becomes just as impudent as Catherine after Catherine’s

death. Young Cathy (Catherine’s

daughter) follows the same pattern. Mind that I find their saucy tongues quite entertaining, and perhaps I

should give Emily the benefit of the doubt: she may have meant to represent

that under trying, abusive circumstances, sweet, cultivated women will all

become a bit mad!

I’m blown away far more this time than when I read it as a girl—both times the same copy, a now falling-apart Watermill Classic paperback edition, put out in 1983, that I received with my Troll book order at school. I still find it odd that books can be reprinted with no notation on the copyright page of the original publication date. At least this edition does mention in the About the Author section that Wuthering Heights was actually first published in 1847. Emily would likely have produced many other great works if she hadn’t died the next year in 1848, age 30—her life snuffed out all too early, like so many of the novel’s characters. In fact, it almost seems that someone was truly making a ‘clear house of it’ for all the Brontë’s around this time.

Even though I think it a monumental work of art now, what I recall most about it from my girlhood is arguing that Jane Eyre, by Emily’s older sister, was a far better story (my own younger sister disagreed). I suppose I should probably reread Jane Eyre now, too, to see if I still feel the same way! At the time, I found it difficult to connect with the characters in Emily’s novel of eccentrics, whereas I completely identified with poor, relatable Jane Eyre. The only truly reasonable person in Wuthering Heights seems to be the motherly housekeeper Nelly Dean, who serves as the narrator of much of the story, and I certainly didn’t identify with her as a preteen. Perhaps not so much now, either, but more than before. I can also relate to the passions of the characters better, too, of course. Overall, though, I regard Wuthering Heights as gripping, highly dramatized entertainment in comparison with, say, the social realism of Jane Austen.

|

| Emily Brontë |

Now, as I so like to do, let's shift gears a bit to chat about possible

inspirations:

First, there is the fairly shocking incident of Catherine’s coffin

side being removed so that their bodies could lie together in the grave. This is perhaps inspired by a true story: King George II commanded similarly for his wife Caroline’s coffin--for the side

of it to be removable so that his coffin to adjoin hers. She predeceased him, and

he wanted to eventually lie with her in their resting place, undivided for the

rest of eternity (he died in 1760). So perhaps that true story inspired

Emily!

I mentioned before in my blog about Northanger Abbey

how Wuthering Heights seemed to have been inspired at least in part by the protagonist Catherine’s

character, especially, even having the same name—only, ironically, it’s set a

little before Northanger Abbey, as if it could be Northanger Abbey’s

inspiration!

The relatively happy situation at the end of Wuthering

Heights for Cathy reminded me of a similar romantic scenario in one of my

favorite novels (at least it’s a favorite book beginning), I Capture the Castle

by Dodie Smith, in which a young, scorned farmhand turns out to be far more

intelligent than he seems at first. Hmm,

that also makes one think of the film The Princess Bride, which takes it

to an entirely different level!

Finally, consider Linton Heathcliff, Cathy’s whiny, spindly

cousin, as the inspiration for the young, crippled master of the manor, Colin Craven (Mary’s

cousin), in The Secret Garden (1911) by Frances Hodgson Burnett.

I truly enjoyed Wuthering Heights—Emily Brontë’s

singular lifetime achievement. She accomplished in her twenties what most

writers can never achieve. What a stunning cast of characters. What an

impossibly passionate tale.

.jpg)